By Ibrahim Mansaray

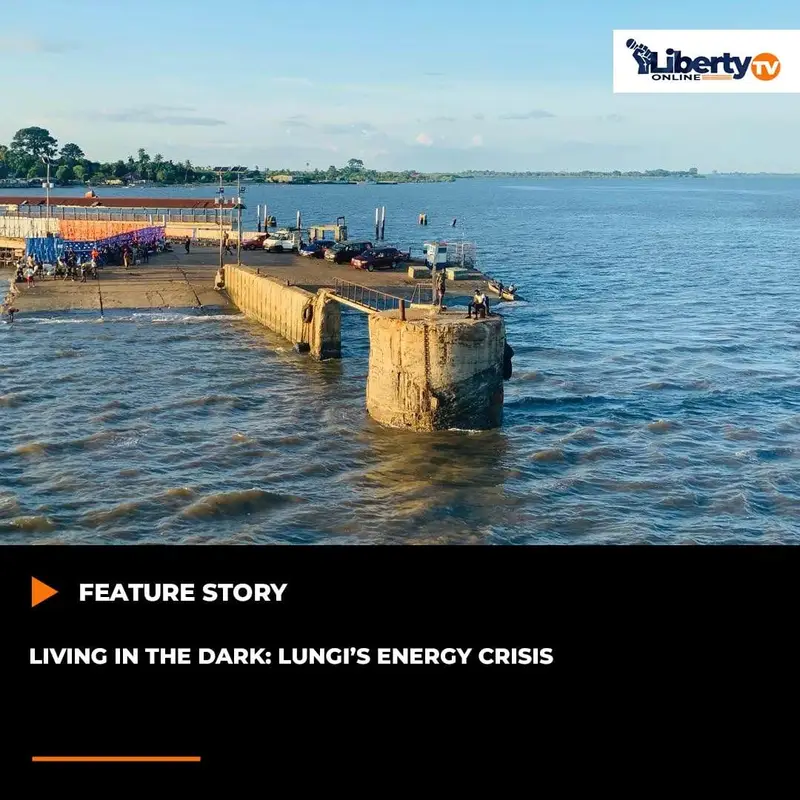

As the last ferry from Freetown docks in Lungi, people making their way to the northern town are greeted with the darkness that covers its flat land and beautiful beaches.

Nightfall puts a hold on almost all activities of most Lungi residents as people go to bed in the lightless settlement, which hosts Sierra Leone’s only international airport.

Lungi holds profound significance in efforts to end Sierra Leone’s civil war, being the very land where 3,000 weapons and hundreds of rounds of ammunition were destroyed by the National Committee on Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration, marking an end to the country’s decade-long civil war. This was followed by the declaration of an end of the war by then President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah with the words: ‘war don don!’.

23 years later, Lungi residents continue to feel neglected, especially in the last few years, thanks largely to growing economic hardship and lack of basic services like reliable power supply.

The incredibly unstable power supply in Lungi has left residents with no choice but to restrategise their activities to fit into their realities.

Rugiatu Hassan, 40, a trader in chicken and other frozen foods has had to make a painful adjustment and cut down on the scale of her business as she struggles to preserve what she sells. “I used to buy plenty of cartons of chicken wings, legs and sausages from Freetown, but I can no longer do so for fear of making a loss,” Hassan told Liberty Online Tv. “There is no light to preserve the products.”

Hassan’s plight represents that of thousands of residents for whom darkness has become normal since 2019. All aspects of life have been made difficult for the people of Lungi, including livelihood, safety and communication.

The effect of blackout is also felt in Hassan’s home where she and her children rely on rechargeable devices that dimly light their house for them to carry out their nightly activities such as studying the kids.

Liberty Online Tv also heard reports of children studying out in the cold under solar street lights.

Fallah Sakilla Fatorma who moved to Lungi in 2006 and settled in Kingsway, a government-owned and controlled area, recalls life before the blackout. “We used to access electricity for at least 18 hours,” he told Liberty Online TV. “It is particularly disturbing for us because we enjoyed it before. Now it’s either not there or unstable.”

Without light at home, Fatorma relies on charging his phone at charging centres for a fee. “Sometimes I go to collect it and I get told that it is not yet charged because there is no space,” Fatorma said.

Lamin Sesay also known as “Blackie”, who owns and runs a tailoring shop at Tintafor Market, one of Lungi’s most popular business places, is forced to increase his expenses. “Because there is no light, I don’t have a choice but to buy fuel. My business runs on generators.” Under such circumstances, he said, “I don’t think we can grow.”

Lungi bears the brunt of Sierra Leone’s energy problems. The energy sovereignty which is said to be a goal for the government is still elusive with the sector ridden with cosmetic solutions, outdated electricity infrastructure and corruption.

In an interview with AYV TV, the Chairman for the Presidential Initiative on Climate Change, Renewable Energy and Food Security, Kandeh Kolleh Yumkella, admitted that the biggest debtor to the Electricity Distribution and Supply Authority (EDSA) is the government.

In 2024, then Minister of Energy, Alhaji Kanja Sesay, was reported to have asked EDSA’s Director General to start disconnecting Ministries, Departments and Agencies. This was after the debt owed by MDAs reached a staggering Le 450 billion (old denomination).

Sesay later resigned. Reasons surrounding his resignation were not officially made known but were reportedly on grounds of being undermined by the Finance Ministry, according to family sources.

The challenges with electrical infrastructure add to the problems. Yumkella also said the metres used around the country are substandard, allowing room for electricity theft. “Over 60,000 (homes) don’t pay electricity bills according to a study we did,” he said.

For people in Lungi, they have to pay charges whether or not they have access to electricity.

Thomas, who visited Lungi from abroad, said he spent 37 days in Lungi, and only saw light for five hours.

According to residents, the excuse for the lack of electricity has always been the same – lack of fuel, every time.

The Director of Communication at EDSA, Sahr Nepoh, said the current lack of electricity in Lungi is as a result of issues with the thermal plant, which he says have almost been resolved. However, Nepoh blames residents for the electricity challenges.

“Lungi used to have light until the people destroyed almost all their transformers,” he told Radio Democracy. He also accused Lungi people of tampering with their metres to the extent that 70% of metres no longer work.

Nonetheless, he says, “there is light at the end of the tunnel” referring to an ongoing project to improve power supply in Lungi.

The Political Side

Lungi, like many places around Sierra Leone, is embroiled in the political divide. In the 2018 general elections, the town elected officials of the All People’s Congress (APC), Sierra Leone’s main opposition party, to all but one of its seven wards. The two constituencies also elected APC politicians as Members of Parliament.

The first past the post system would later be replaced by the District Bloc Proportional Representation System which would result in Lungi hosting three of Port Loko District’s Members of Parliament, including one from the ruling Sierra Leone People’s Party.

Despite this, Blackie, the tailor mentioned earlier, said they still feel neglected.

The dissatisfaction with the neglect has been expressed before.

On August 10th 2022, Lungi was among several places, including the capital Freetown, where massive protests erupted, resulting in the death of both civilians and security forces.

The protests in Lungi were staged outside the airport, where protesters accused the government of summary dismissal of its sons and replacing them with government supporters from the South, a government stronghold.

The government called the protests “terrorism at the highest”, and President Julius Maada Bio, in a national address, accused the APC and People’s Power in Politics (PPP), a coalition of opposition parties, of inciting the violence.

Some of the protesters were later arrested and charged with various offences including riotous conduct and unlawful processions.

There has since been relative calm in the township, but Augusta Senesie, a student, thinks that when people feel neglected, peace is not sustainable.

“People are not happy at all and this does not mean well for peace,” she said. “It’s unfair.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, one of the country’s Transitional Justice mechanisms, listed neglect as one of its primary findings on the causes of the conflict.

“Prior to 1991, successive regimes became increasingly impervious to the wishes and needs of the majority. Instead of implementing positive and progressive policies, each regime perpetuated the ills and self-serving machinations left behind by its predecessor.” (Volume 2, chapter 2, page 30, section 42,)

![]() SAFTY CONCERN

SAFTY CONCERN![]()

Residents of Lungi now sleep with one-eye closed as the darkness provides cover for thieves. Fatorma had once been robbed.

“One morning, I was going to supply bread around 5 a.m. when some young men attacked me and took everything from me,” he told Liberty Online TV. “If there was light, this could not have happened.”

Another woman who asked only to be referred to as “Zainab” said: “we hardly get enough sleep these days. Almost always the threat of burglary is there.”

In September 2023, the Lungi Police division engaged in Community Policing after a surge in crime rate. Some of the common offences according to police, were larceny, sexual penetration, and drug related offences.

Police said that half of inmates at the Port Loko District Correctional Facility at the time were from Lungi.

This, Zainab asserted, could be as a result of the neglect.

Resorting to Solar

As the blackout continues to plague Lungi, residents are now using solar energy to light up their houses. The environmentally-friendly solution, however, costs a fortune, making it unaffordable for many.

Ansu Kamara says he spent around Le 50,000 to do a 2.5kva solar installation. Unlike Ansu, thousands of residents can’t afford that for their homes, leaving them to a very rudimentary way of living.

Families who feel they can afford it in the near future are now saving up to return power to their homes.

Aminata Abu Bakarr Kamara, a journalist, wrote in her article titled “Lungi’s persistent blackout: what are our representatives doing”: “The persistent blackout in Lungi is a national embarrassment that needs immediate attention.”

Kamara’s call to action is similar to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) recommendation on bringing government and service delivery to the people.

“For many years, successive governments have failed dismally to meet the basic needs of most Sierra Leoneans, particularly those outside of Freetown. The present Government and future governments must be seen to be establishing infrastructure and delivering health, education, justice and security services in all Provinces.” (Volume 2, Chapter 3, page 156, section 248)

Lungi residents look forward to service delivery from the government, starting with energy and other basic amenities.

“The infrastructure is there, the government just needs to provide what’s needed to power the plants,” one resident said.

Yumkella, the acting head of Sierra Leone’s energy sector, said there is a World Bank funded project which in 12 months will generate 30 megawatts for Freetown and 10 for Lungi. This suggests that stable electricity in Lungi is still distant.

“We don’t deserve this,” Hassan said, looking very disappointed.

This story is brought to you with support from the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) through the Media Reform Coordinating Group (MRCG) under the project ‘Engaging Media and Communities to Change the Narrative on Transitional Justice Issues in Sierra.’